April, 2018

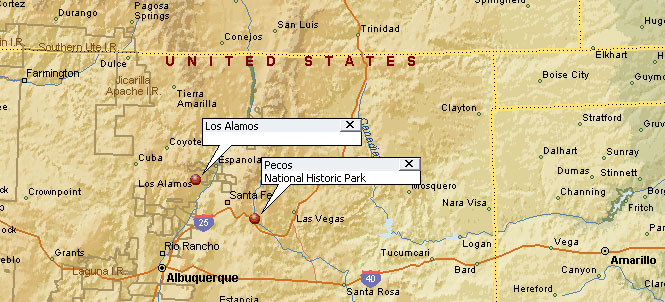

I've been all around Los Alamos, but had never made it to the mesa to see what's up there. Besides Los Alamos, there are several other things to see in the area.

New Mexico

New Mexico

If you were looking for a place to start a super-secret research center and laboratory you'd be hard pressed to find a place as ideal as the Los Alamos Mesa, northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico.

If you lay your hand flat on a table and spread your fingers, you'll have an idea of how these long, thin mesas are arranged. There's just one road up from the Rio Grande Valley, and a deep gorge between adjacent mesas.

The guard tower hints at the security that was once in place. Today, traffic on the road into the town breezes through, but during the war, there was a heavily secured checkpoint.

There are several museums in town, but the Bradbury Science Museum is the one that counts if you're most interested in the development of the two atomic bombs that were dropped during World War 2.

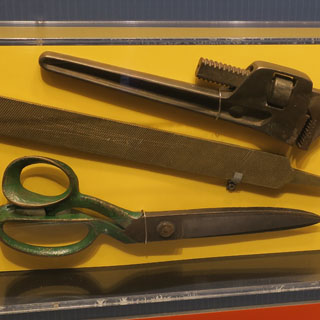

Beryllium tools (to avoid sparks) and the detonation device on the "fat man" bomb.

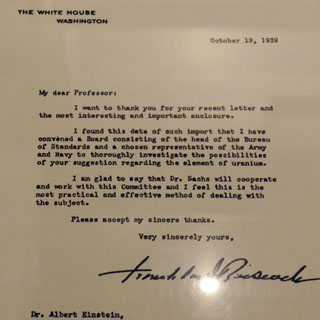

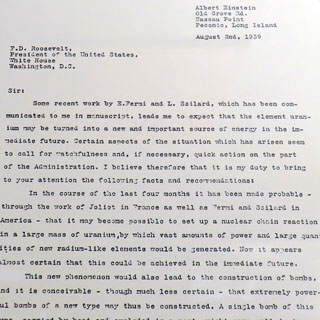

Two important letters: Einstein's letter to president Roosevelt detailing the possibilities of Atomic power and the likelihood that Germany was already working on an Atomic bomb, and Roosevelt's answer, which initiated the process that eventually became the Manhattan Project.

It's quite a good museum; the many displays assume a level of intelligence from the visitor and if you want more depth, you'll find that too.

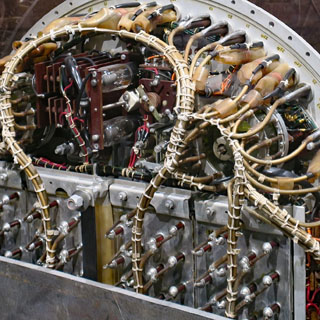

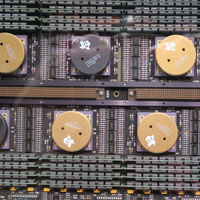

This laboratory has always been a leader in powerful computers. Even the old things are still pretty amazing by today's standards.

If you want to run a mathematical simulation of a nuclear device, you'll need the proverbial "warehouse full of computers." Run-times take months.

These two bombs and the underground testing equipment is why this place is here.

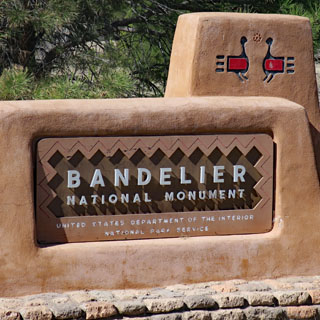

Before you try to figure out the unusual name, know that it's named for Adolph Bandelier, an anthropologist who first studied this site in the 1880s.

The park is quite large; only a small bit has roads. The visitor center is down there in Frijoles Canyon.

In busier times (but, not now), the park is only accessible through a shuttle bus. Clearly, parking is limited.

The trail (Main Loop Trail) that leads to many of the old dwelling sites leaves from the visitor center. Full out-and-back is just about two miles.

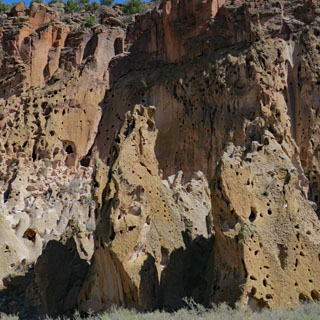

People have lived here for more than ten-thousand years. It would be a mistake to assume that the same people lived here all that time; some leave, others take their place.

Frijoles Creek flows year round, which explains much of the "why here?"

Today, we don't see the multi-level buildings that extended outward from the walls of the canyon. This was a large settlement.

To reach some of the site requires taking several ladders. The rungs and the ladders, themselves, are well secured with bolts. If you fall, it's your fault.

I'm now walking the other direction from the visitor center--towards the Rio Grande River, but still along Frijoles Creek.

Upper Falls, Frijoles Creek.

There is also a "Lower Falls" but that is further down the trail, which was closed for being in poor shape (and apt to have you sliding down the side of the canyon). Eventually, the trail reaches the Rio Grande River.

Valles Caldera National Preserve

Valles Caldera National Preserve

Protection of this land has been an ongoing struggle. It was only passed to the keeping of the National Park Service in 2015.

After what must have been a really, really loud explosion, this thirteen-mile wide caldera was created, along with hundreds of feet of volcanic debris that was spread over hundreds of miles. The last large eruption was 1.2 million years ago, but there have been later, smaller, volcanic events since then (the last about 50,000 years ago).

There are not any paved roads in the preserve, but the dirt road to the visitor center isn't bad (signs request that you avoid the prairie dogs). This time of year, even the dirt road beyond this point is closed.

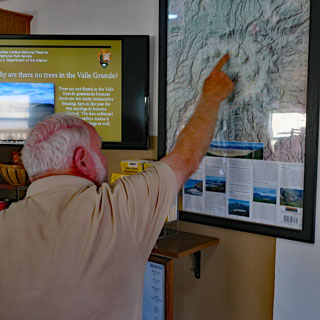

The topographical map that the ranger is pointing to gives a good view of the whole caldera.

Long before the Spanish built a mission here (in the late 1500s) it was the location of the Gíusewa Pueblo. Today the site is maintained by New Mexico.

Pecos National Historical Park

Pecos National Historical Park

The Cicuye Pueblo was here from around the 1300s. The site was renamed "Pecos" by the Spanish (as was the river). It was a site that has always had importance. It's at the west entry to Glorieta Pass, which connects the Great Plains to the Rio Grande Valley (and Santa Fe). If you wanted to travel (with some ease) between those places, you'd be walking through Pecos.

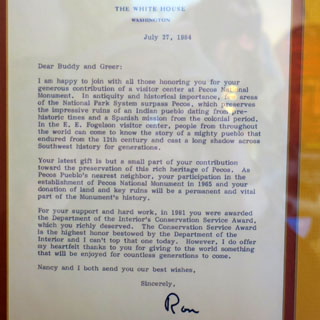

Who knew? Greer Garson (and husband) donated the money for the visitor center as well as much the land that would become the historical park. That's a letter from President Reagan thanking her. She did the voice-over narration for the visitor center film.

This is one of the better visitor center museums for the pueblo settlements of New Mexico.

The first church was built in the early 1600s. It was destroyed during the great pueblo revolt. The new church (the remains of which you see) is much smaller and was built about twenty years after the revolt.

There was a great deal of archeological digging done here in the late 1800s. Things are more methodical, today.

Take note of that mesa (seen from the Pecos pueblo).

Battle of Glorieta Pass, Pecos National Historical Park

Battle of Glorieta Pass, Pecos National Historical Park

You'll need to get the combination to the lock back at Pecos to enter this park. Please lock the gate when you leave.

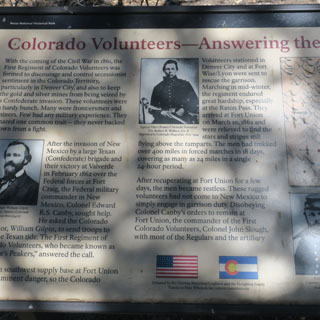

The battlefield has only recently been brought under the protection of the national park system (as is Gettysburg, for instance). While not a large battle (in comparison) it is of tremendous importance to limiting any Confederate spread westward from Texas. That possibility stopped, here.

At the time of the battle (March, 1862) much of this land would have been cleared of trees by local farmers. That detail makes it more difficult to really see how things used to be.

In short:

The confederates had success taking Albuquerque and then Santa Fe as they marched north up the Rio Grand Valley. Their goal was to cross Glorieta Pass and take Fort Union, which was the primary supply base for all the western forts of the United States. If successful, they'd have control of the Rocky Mountain West including the mines of Colorado, with even the possibility of expansion towards California (as was considered).

Opposing them were troops (mostly volunteers) from Colorado who came south from Denver (making incredible time each day during their forced march). Both armies arrived at Glorieta Pass without really knowing where the other was until they came together.

After several battles, and after the Union forces were pushed eastwards towards Pecos, the Union Commander split his forces and ordered a separate force to climb up the south mesa (that photograph you saw above) and go around the Confederates to attack their right flank.

The battle in the valley (at this site) was hard-fought, but ended with the Confederates on the field-of-battle with the Union soldiers pushed further east. A Confederate victory? No. That other force who had made the remarkable hike up and over the mesa, actually went too far, and when they descended they were overlooking the entire supply train of the Confederate army. They destroyed all of it and scattered the horses and mules, as it had been left largely undefended.

At that point, the Confederate force had no choice but to withdraw back to Texas. Battlefield victory or not, if your supplies have all been destroyed, you cannot go forward; you've lost.

The path through the battlefield is well defined, and there are plenty of signs explaining things.

You don't need to go far east from the Rocky Mountains to be in the vast short-grass prairie that stretches for hundreds of miles. No fences, few roads, very few towns. You will see Pronghorns.